Rosset and Grey

Words by Daniel Bosley; Images by Aishath Naj

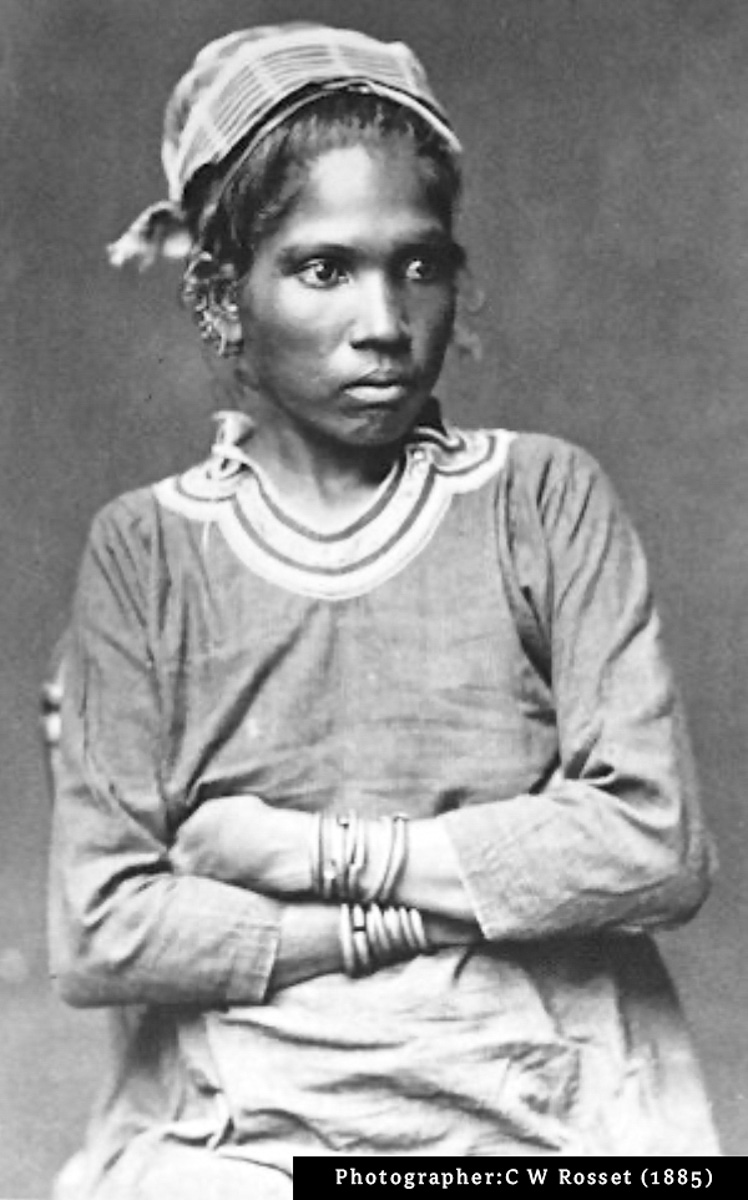

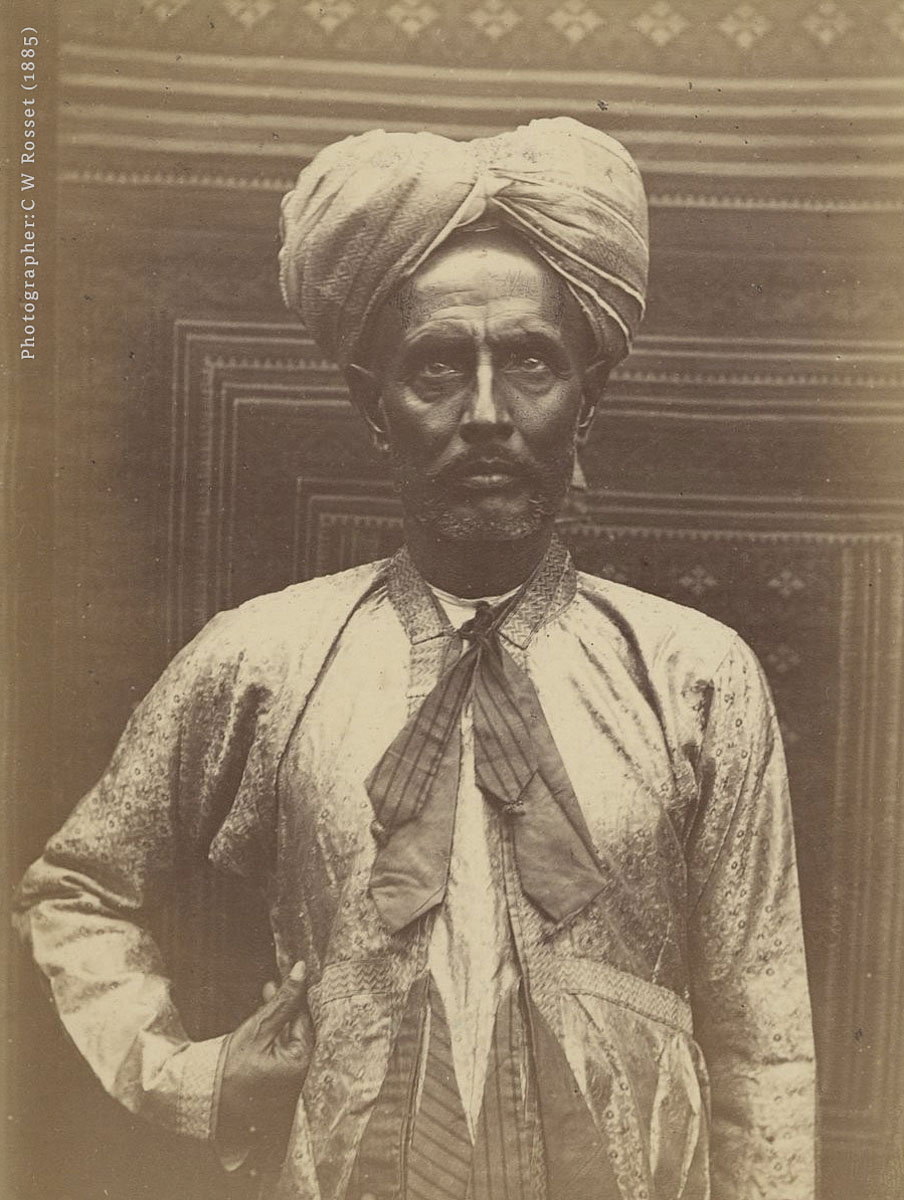

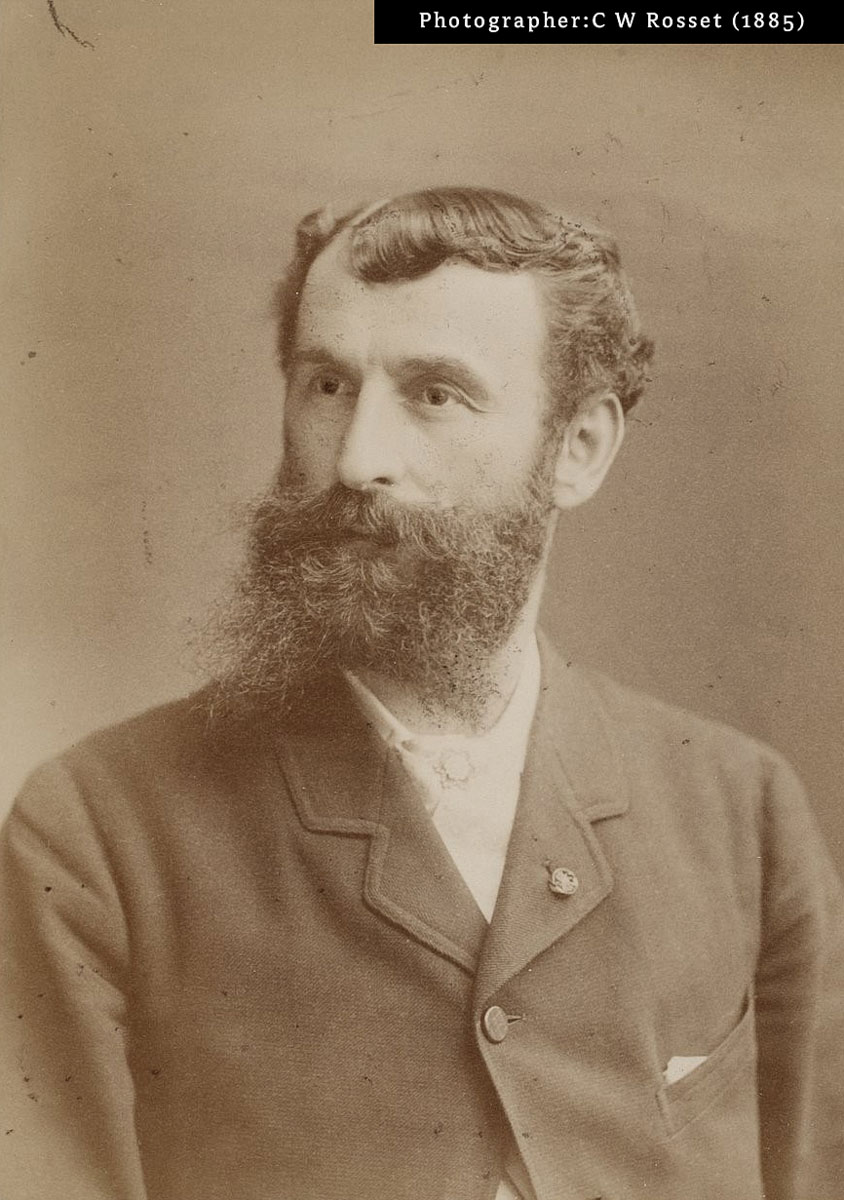

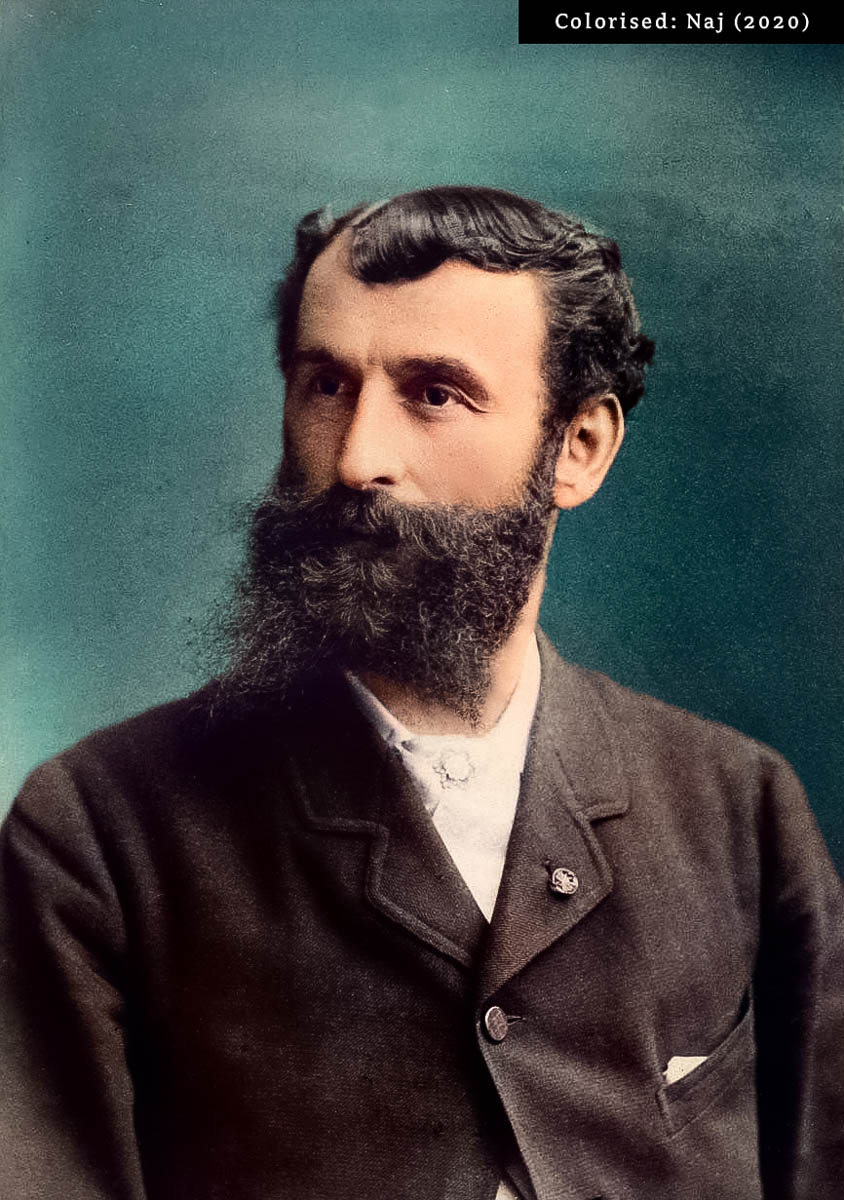

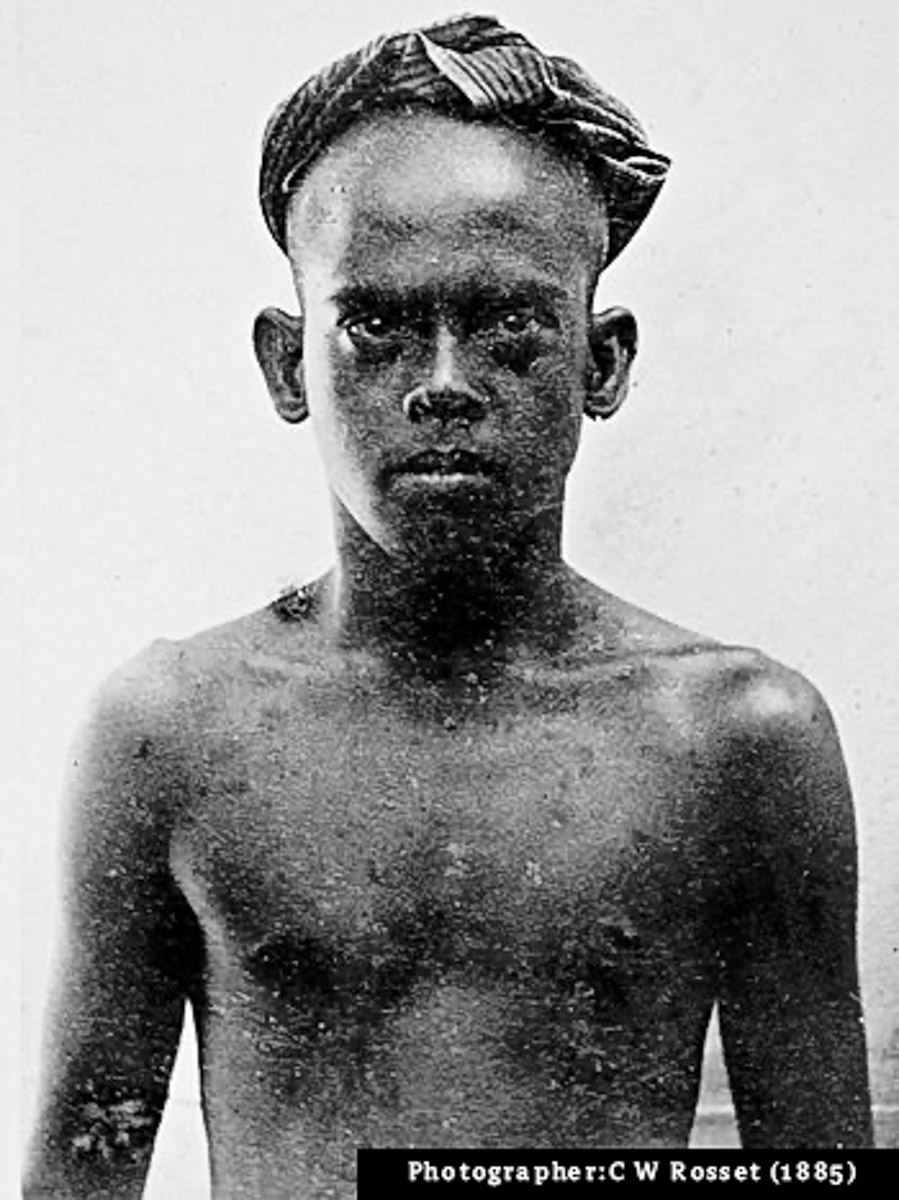

Carl Wilhelm Rosset is generally believed to have been the first person to produce photographs of Maldivians, during his two month stay in Male’ in 1885. It’s hard to know this for sure – we’ve only just finished counting the islands – but as visitors were rare back then, and photography still in its formative years, it’s a fairly safe assumption.

As curious foreigners and photography became more common, pictures of Maldivians – while still rare – are more frequent after this point, but the sheer difficulty of taking and preserving such images was indicated by H.C.P. Bell’s mixed results more than 30 years later. In short, Rosset’s images remain some of the most beautiful and impressive Maldivian portraits ever taken…and it seems that he had to work for them!

Rosset’s trip from Ceylon – aboard an English steamer helpfully named ‘Ceylon’ – had been delayed by twelve months due to a “combination of accidents”, which then combined with geopolitical events to ensure he met with a fairly frosty reception, even after waiting for the fair weather of the NE Monsoon. For, as Rosset started packing in Ceylon in August 1885, on the other side of the Indian Ocean Chancellor Otto Van Bismarck was sending four warships to Zanzibar, demanding the Sultan Barghash hand over his empire as part of the European powers’ mad scramble for Africa. With passing ships bringing stories of these troubling events to Male’ before the English dropped off Rosset, he was instantly considered by many to be an agent of European imperialism. Among these was Sultan Ibrahim Nooradeen; or at least those around him.

The resulting tension inevitably contributed to Rosset’s scathing description of the Sultan:

His rule is absolute; and although he has ministers whose advice he seeks on any occasion of importance, he seldom if ever profits by their wisdom…He is very adverse to any intercourse with foreigners, especially Europeans, whom he either refuses to see at all or keeps waiting, perhaps, for weeks before granting an interview. At the time of my visit, this cautiousness had been very much increased by the recent arrival of news from Zanzibar…and he consequently fancied that my visit had some ulterior and political design which he could only frustrate by detaining me in Male’ until the Ceylon arrived to take me away again.

For detained Rosset was; not literally but practically, with permission to visit the surrounding islands refused.

This stalling tactic seemed to have been a common one for some time, with Francois Pyrard having noted – almost three hundred years before – that the Sultan would delay stranded foreigners, knowing they would eventually be ‘taken away again’ by the dreaded Maldive fever, thus defaulting their ships and cargo. Estimating that 60% of islanders were sick at any one time during his visit, and acknowledging that almost all visiting Europeans died from malaria, Rosset himself was confident his extensive travel and good diet would protect him. (‘Yeah, let’s see how that works out for you’, thought the Sultan).

This uncomfortable relationship with the sovereign may explain why, although Rosset was allowed to take photographs of some islanders – which the Sultan reportedly liked – Nooradeen refused to have his own image captured. Fascinatingly, historians have since argued that this may be because Rosset didn’t meet Ibrahim Nooradeen at all, but was instead presented with a double. This tactic is said to have been one advised by influential mullahs who, despite 300 years having passed, were paranoid that ‘Nooradeen I’ might be converted into ‘Dom Manuel II’ by marauding missionaries.

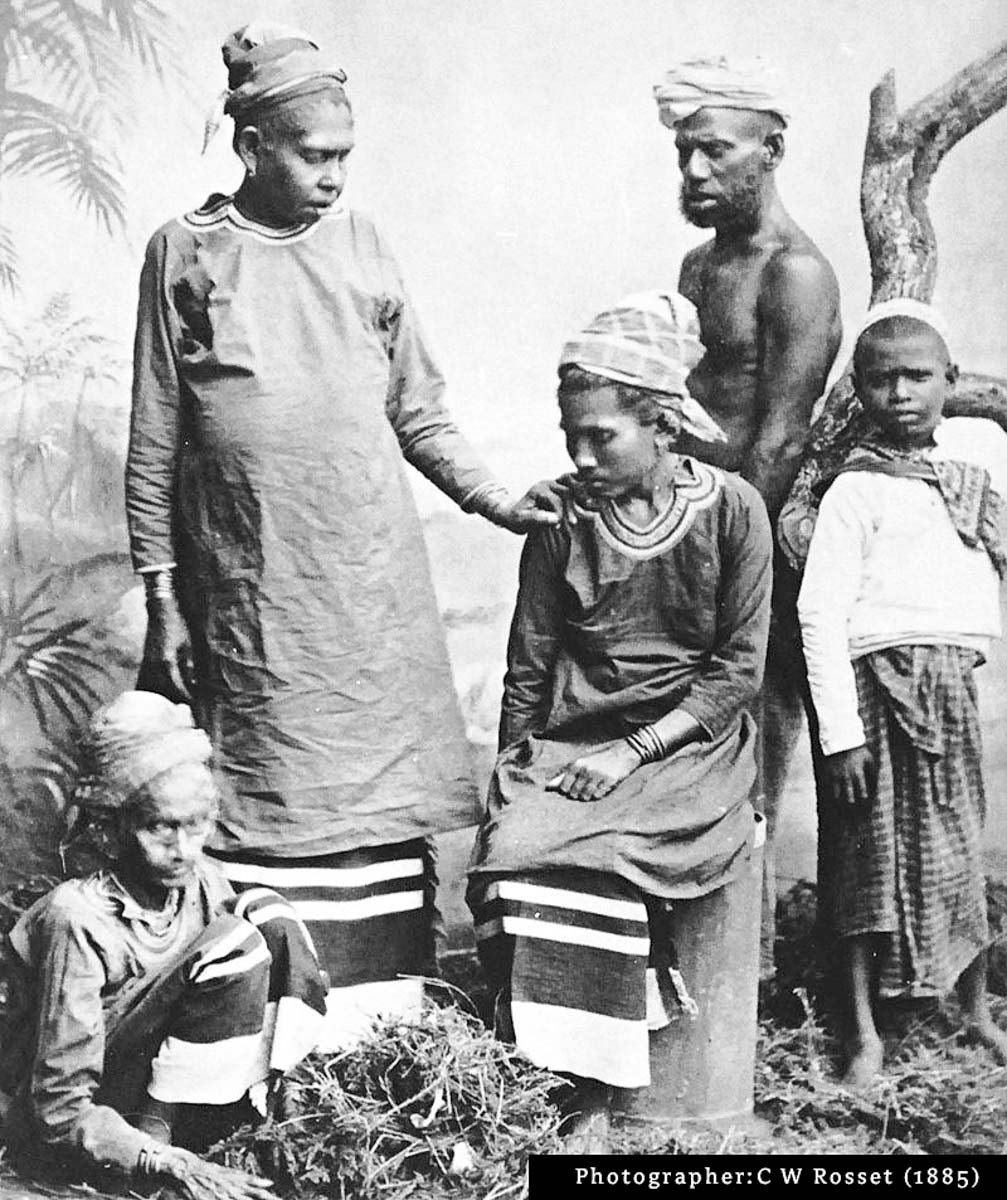

Reported prohibitions on anyone interacting with outsiders may explain why the identity of most of those Rosset was able to photograph appears a mystery. It seems unlikely there was much of an accompanying interview, or even an answer to ’why that strange foreigner is pointing that thing at us?’

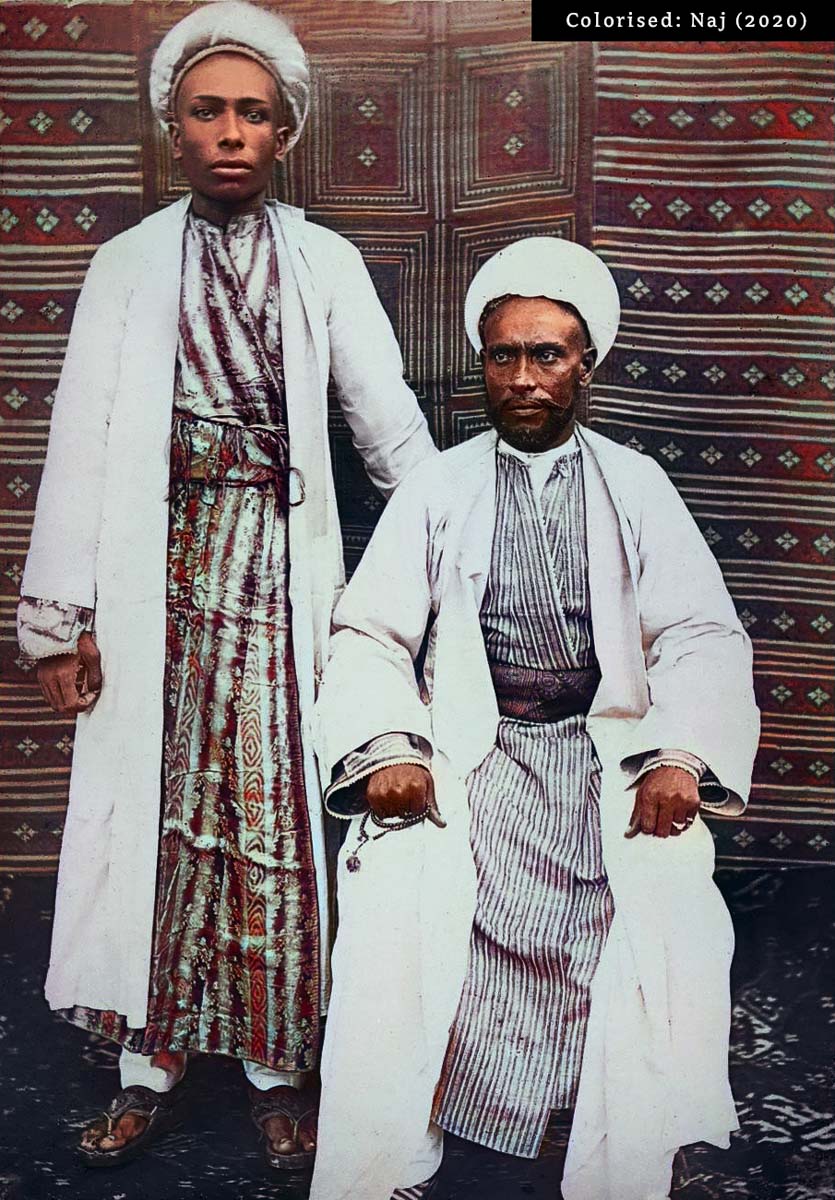

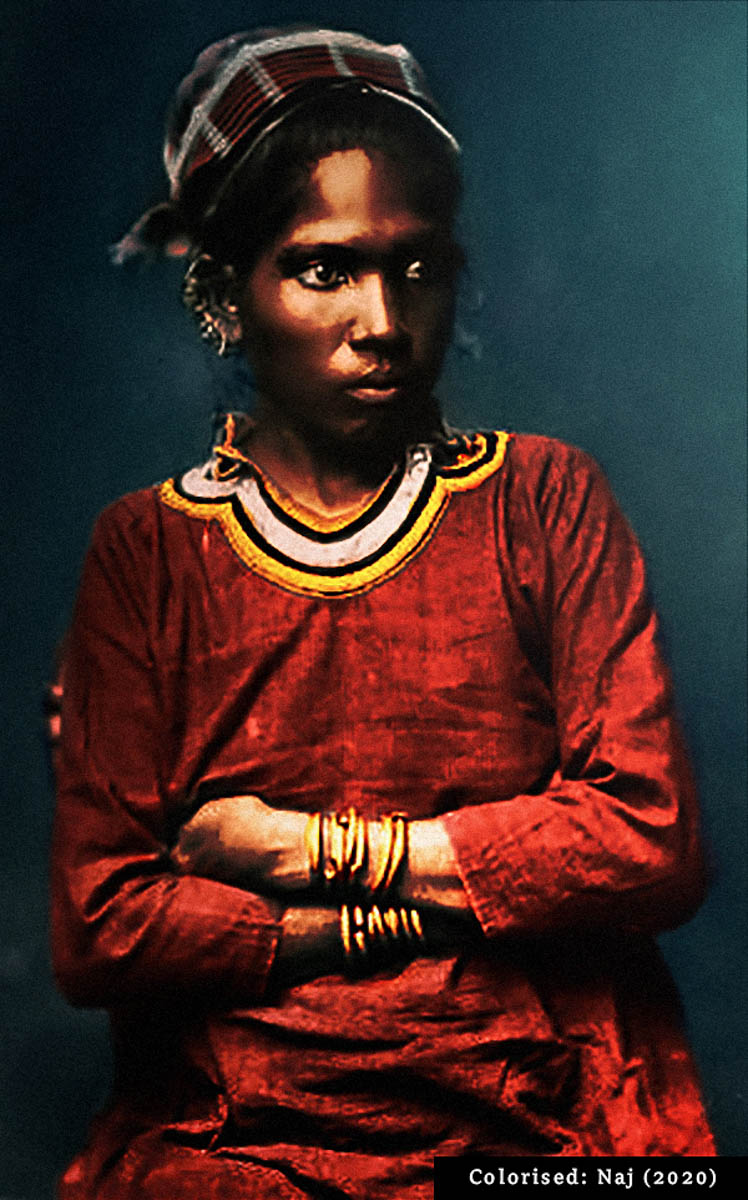

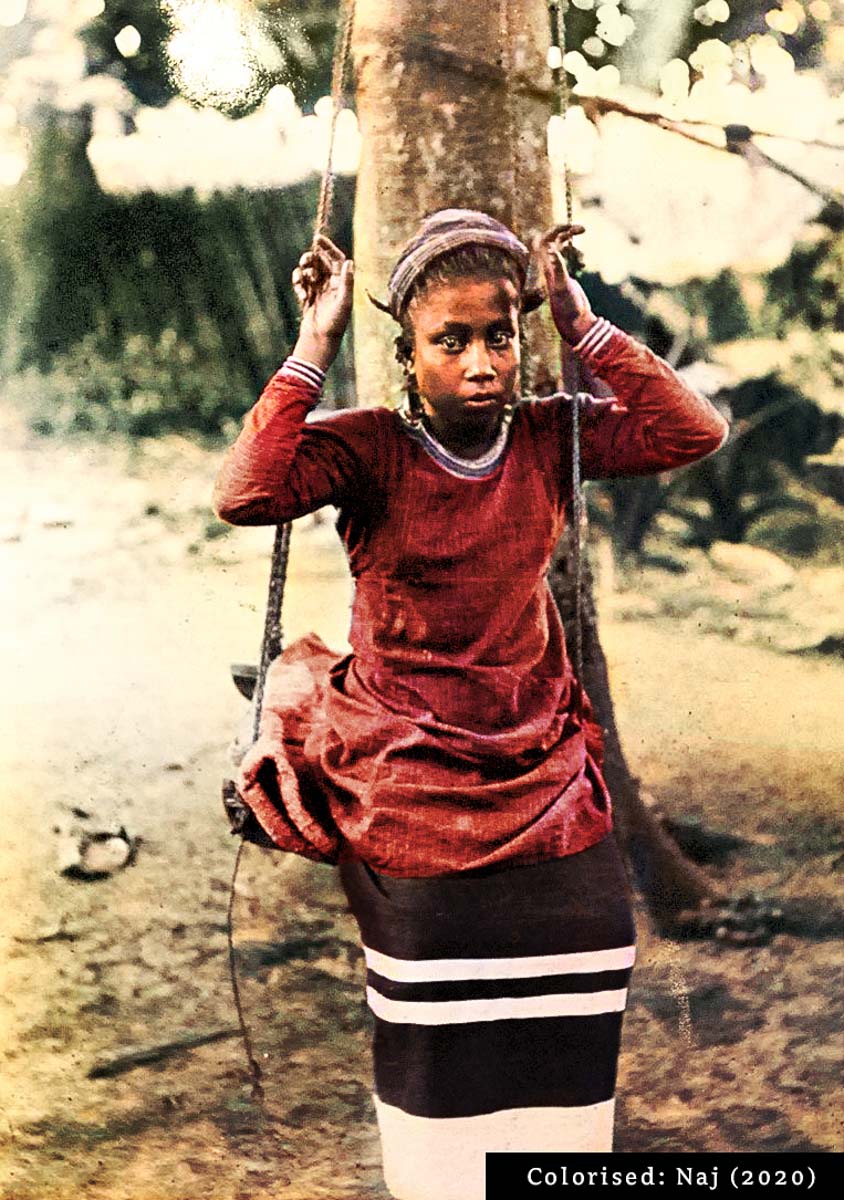

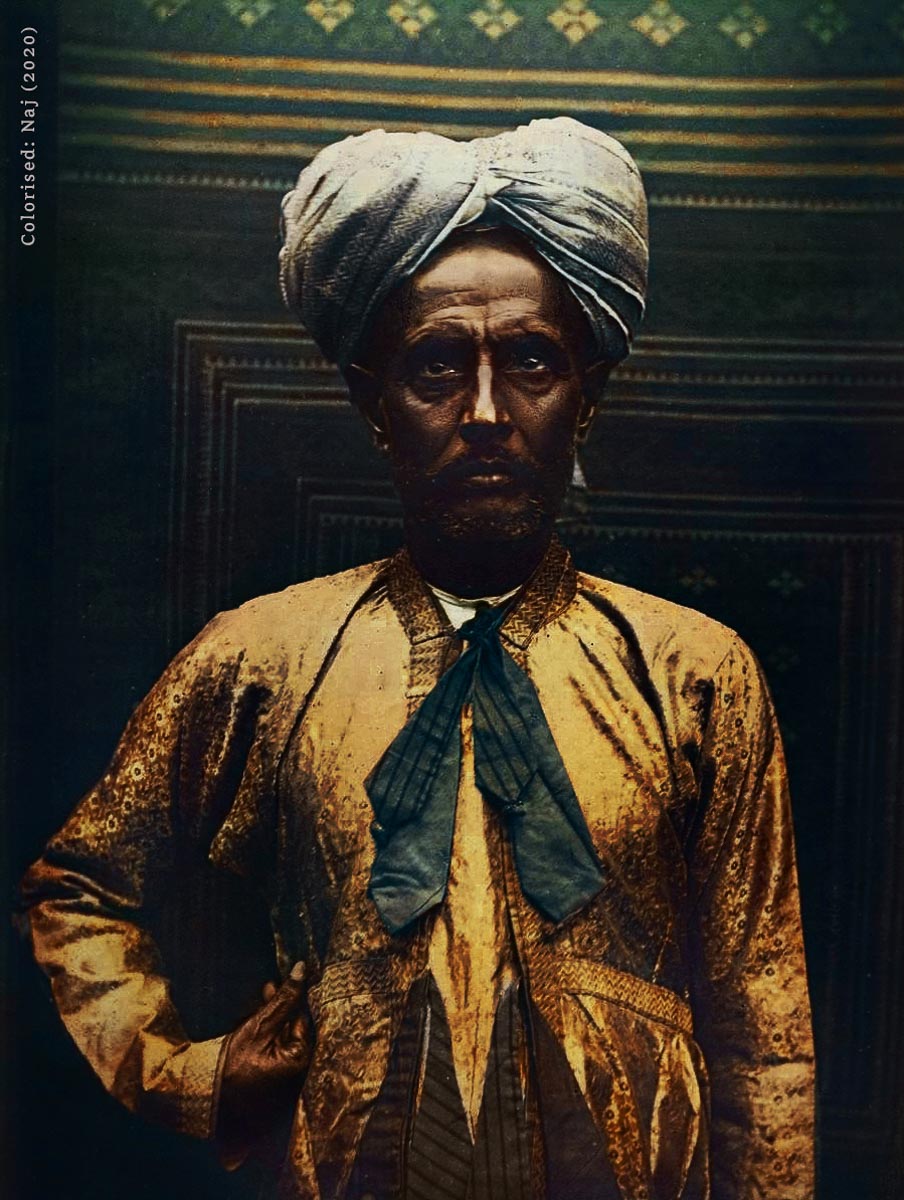

Rosset’s description of Maldivian dress is brief, but notes from Bell’s first visit 6 years before, and the always-relevant Pyrard, suggest that the feyli was a ‘chocolate brown’ colour with black and white stripes, and the libaas would have been the famous red, with gold and silver neckline. None stated explicitly weather other- coloured libaas’ were commonly worn, but we couldn’t really see why not, if cloth was regularly imported. As for the head-kerchiefs, Bell suggested these may have been a relatively recent Male’-fad, and were also red.

Perhaps the most important feature highlighted by the colourisation of these photos is the jewellery, particularly the multiple piercings of the ear which Pyrard had described in graphic detail so many years before. While the Frenchman had said the display of gold and jewellery was a sign of wealth, and permitted only to persons of privilege (beyfulhun), Bell reported that fashion had since become less restricted. This ultimately makes it unclear what the social rank of Rosset’s subjects may have been, but it seems likely that residents of the capital, nominated to be photographed, would not have been of insignificant status (our roundabout way of saying ‘dunno’).

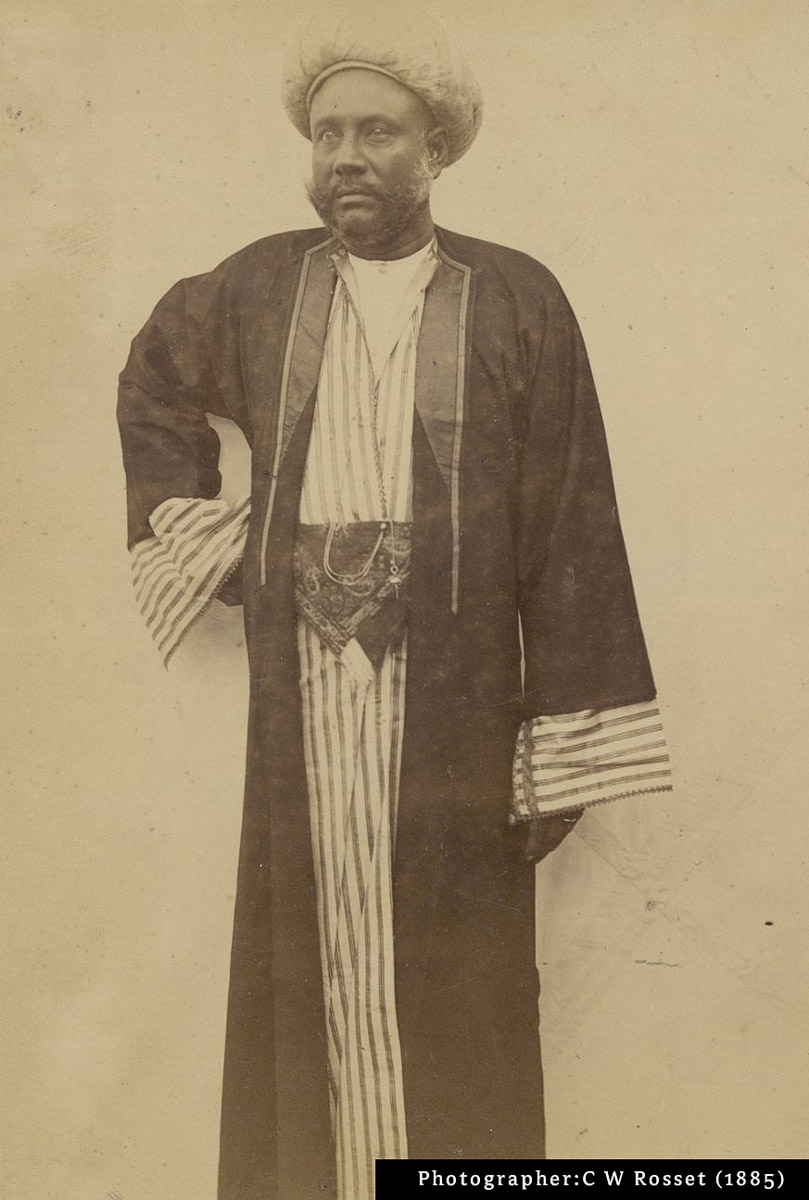

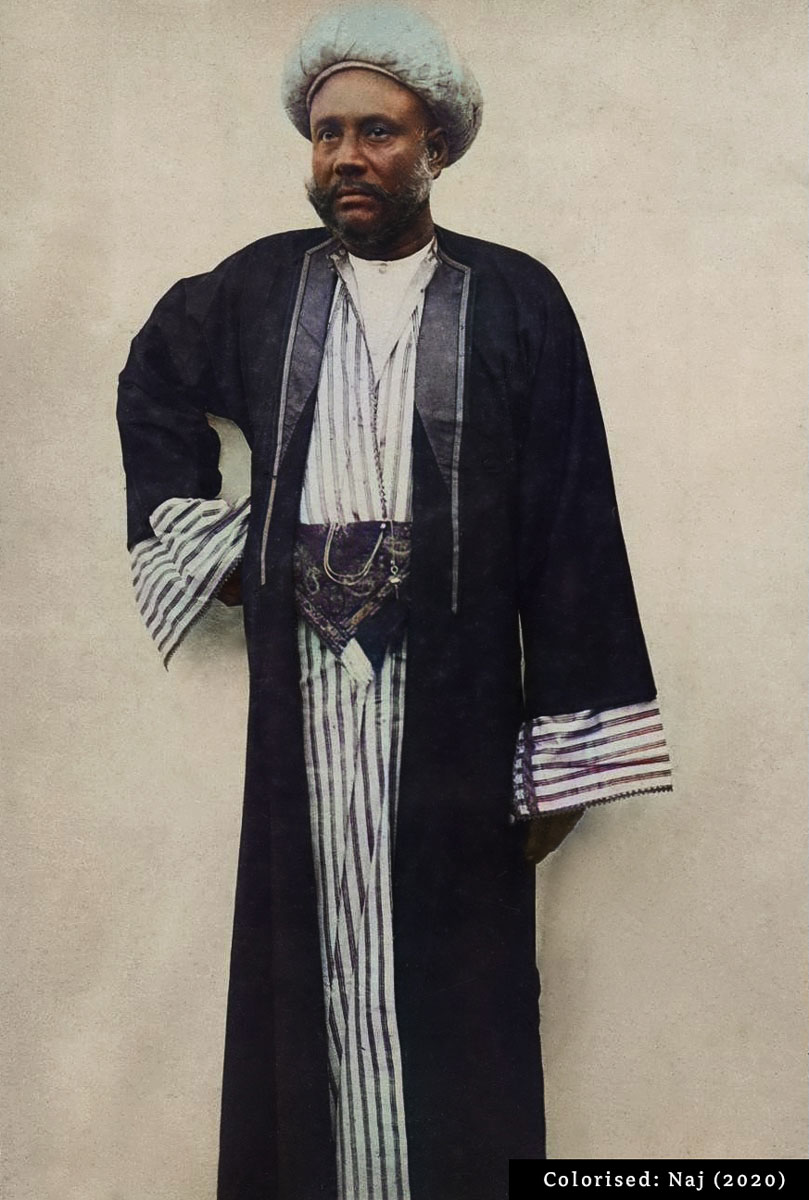

In a rare stroke of good fortune, Rosset was able to obtain some more assistance from the Prime Minister, Athireege Ibrahim Didi, who was himself a great anglophile, having received an English education in Ceylon (apparently also a Europhile: described by Rosset as ‘loveable’). The PM was able to gather the artefacts and information Rosset required from surrounding islands, after the ’Sultan’ had been unwilling to trade items from his palace for the German’s gun (‘why is that strange foreigner pointing that thing at me?).

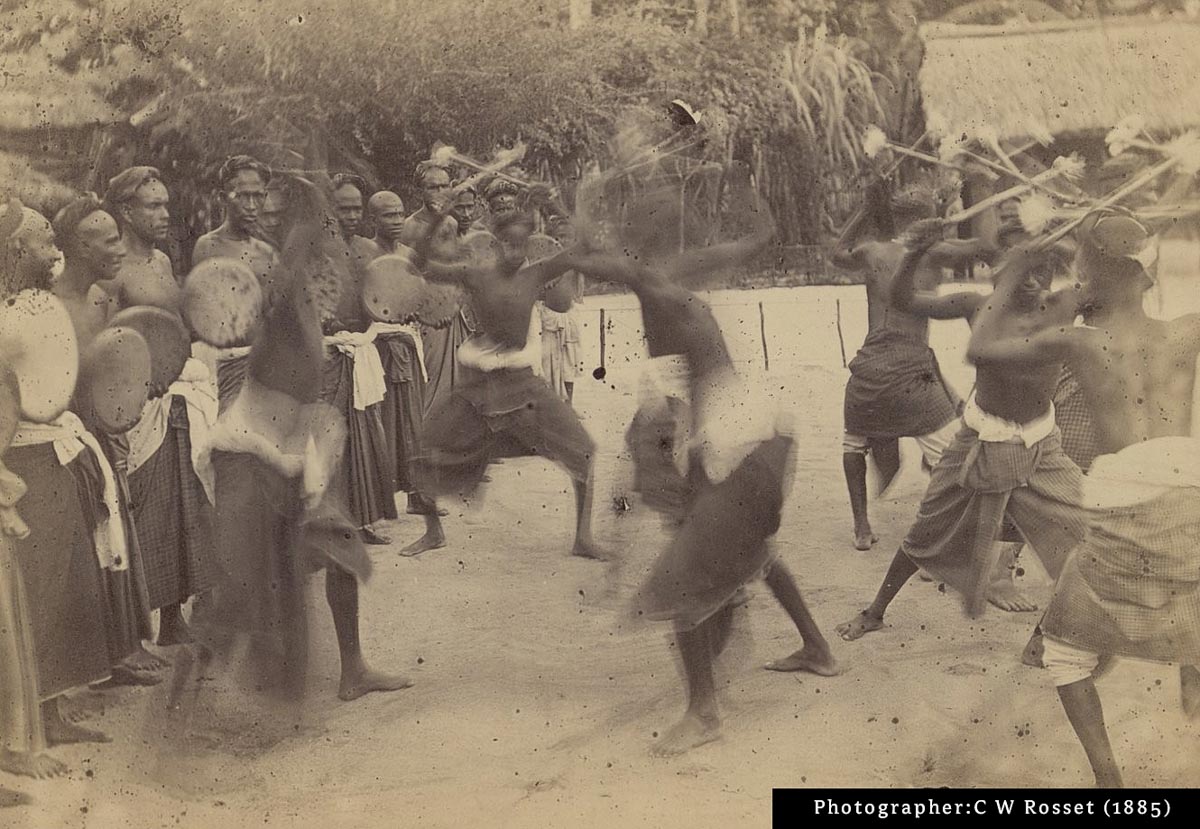

He was eventually granted permission to visit the outer islands, just as he ran out of time to point any more things at any more islanders (touche’…‘Nooradeen’). Arrangements were already in place to display what he had captured during the ‘Colonial and Indian Exhibition’, due to be opened by Queen Victoria in London six months later. The Prince of Wales stated that the event was designed to strengthen the bonds of the empire, on which the sun never set. The Maldive Islands were still not officially a part of it, though their inclusion was evidently on the horizon.

“Specially interesting, in our estimation, in the very valuable collection of objects from the Maldive Islands, in Case M, lent by Mr C.W. Rosset. The portraits of these islanders show them to be a dignified and self-possessed people, while their weapons, silver and gold jewellery, cloths and other manufactures show them to be well-advanced in art and civilization,” patronised the Times of London [fourth column]. The exhibition received 5.5million visitors, though, thankfully, no Maldivians were among the ‘living exhibits’ on display.

Ibrahim Didi would also become a firm friend of H.C.P. Bell, who later described him as “quite the most able Servant of the Crown in the islands’ history”…though, in hindsight, it’s not entirely clear to which crown he was referring. The British reported that Rosset’s visit had contained no hint of political intervention, as they happily carved up Africa, soon splitting Zanzibar’s empire between them. Nevertheless, due to rising tensions in Male’ between locals and the now well-established Borah merchants – and according to British records, at the strong urging of Ibrahim Didi – the British decided to formalise their de facto control over the Maldives external affairs.

Less than two years after Rosset left Male’ with his photos, Nooradeen’s successor, Muinuddin II, was convinced to sign a formal protectorate treaty recognising the suzerainty of the British sovereign. Didi himself was, by this time, doing a stint of ‘national service’, AKA banishment in Addu and then onto Ceylon, but he’d be back. In Didi’s temporary absence, the new Sultan’s reluctance to sign was described by Bell as “undignified shuffling and needless delay”; others have described it as a gunboat to the head. The available British records are curiously silent on this point, but it seems the misplaced suspicions surrounding C.W. Rosset were perhaps not too wide of the (Bis)mark after all.

The rest of Rosset’s wonderful photos are thought to have been destroyed in Berlin at the end of World War II, when these European imperialists decided to turn their guns on one another.

Wonderful!

Wow what a fantastic era!