Darkness & Didis

Words by Daniel Bosley; Pictures by Aishath Naj

Even the Maldives’ relatively recent past is often shrouded in mystery, with hearsay and history inextricably melded into what will probably have to remain categorised as ‘stories’.

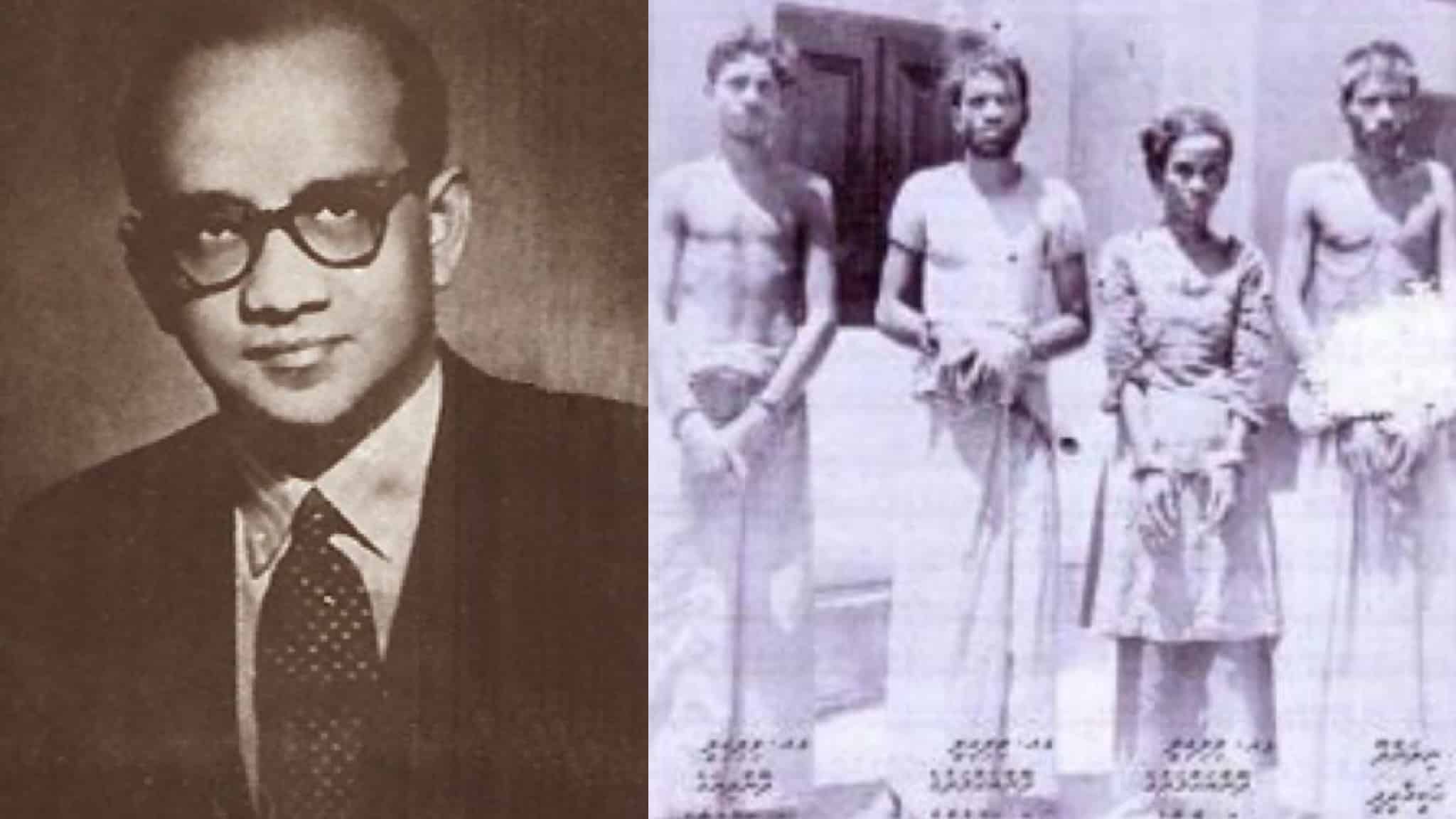

The name of Hakeem Didi is one that remains relevant today, as the last man to be executed in the country, in 1953. More than most, however, his reputation as one of the Maldives best known practitioners of traditional magic (fanditha) has raised his name to legendary status.

Having spent time on Hakeem Didi’s home island of Gaafu Alif Nilandhoo, we found some new details and old disagreements about his life. Rumours and reality continue to rub shoulders in the gloom.

This fictional account of Hakeem Didi’s final days presents just a version of events, and is based on conversations with his friends and family members, as well as on an article from the always-excellent maldivesculture.com.

Hakeem Didi jumped up from the holhuashi with a start, and peered out over the reef at the small boat making its way across the lagoon.

His fellow islanders, reclining in the mid-morning sun by the jetty area of Nilandhoo, eyed their neighbour warily. Talk of politics, fish, and women were interrupted as they watched the famous fanditha man.

“They’ve come for me,” mumbled Hakeem Didi, to no one in particular.

Squinting in the bright sun, he pulled out a handkerchief from his side and flicked it dramatically in the air three times while his fellow islanders gazed on. When finished, he returned his stare to the dinghy, hoping his efforts might be rewarded.

The wind over Huvadhu’s lagoon seemed to grow in strength, a large cloud cast a grey pall over the island. All eyes turned towards the reef and the small boat began to rock violently on the water, rolling up and over the dark waves.

Just as it neared the broad expanse of turquoise over the shallow approach to the island, a huge wave appeared, obscuring the tiny craft from the view of those on the land. Nobody breathed.

After what seemed an age, the vessel reappeared, closer now and moving faster as it rowed across the reef. Breathing resumed, but as eyes were cast nervously sideways towards Hakeem, he had disappeared.

Within minutes, the boat had reached the beach and was hauled ashore by the crowd. A short bespectacled man stepped out, sending a new wave of awe through the gathering crowd. Prime Minister Amin Didi had arrived* to personally investigate the recent death of his atoll chief, Veeru Ali Didi.

In a house nearby, Hakeem Didi threw himself down on the bed, his head in his hands.

“My time is up,” he sighed.

——–

Of all the fandithaveriya in Huvadhu (and there were many), Hakeem Didi had built a reputation as the best, or the worst, depending on who was paying for his services. Indeed, by 1952, many considered him to be the Maldives most powerful sorcerer, able to fill a dhoni with fish, to sink a trading ship or to sink a marriage, seemingly at will.

Veeru Ali Didi was unlikely to have been a keen admirer of Hakeem. For, as the chief of Huvadhu atoll, he was regarded by all as a strong character, but with enmity by the wealthy merchants on the eastern island of Villingili, who would often seek supernatural assistance from nearby Nilandhoo.

Competition between islands had always been a part of life in the atolls, but recent years of famine and growing centralisation of trade had raised tensions further. As Veeru Ali Didi headed across the lagoon from Thinadhoo to Villingili, however, he couldn’t have imagined he would return a dying man.

For while the chief’s vessel sailed across the lagoon, a man named Anees – son of Villingili’s own fanditha man Dhon Ahmad – crouched on the sandy yard of his father’s home, beside an open fire. Glancing around to check he was unobserved, he scratched some Arabic into the flesh of a fish before dropping it into a pot of water over the flames.

Arriving to conduct his rounds on Villingili, the atoll chief was invited into the home of Dhon Ahmadu and served tea, as always. He sipped the brew between mouthfuls of boakiba, filling the gaps with enquiries about taxation and with talk of Male’s energetic leader. He probed subtly for signals of dissidence, unaware of the poisonous evidence already working its way through his body.

Soon after, Veeru Ali Didi began to feel unwell, his limbs grew weak, his speech slurred. Fearing foul play as their chief collapsed, face frozen in a damp pallor, his companions hurriedly bundled him back onto the boat and pointed the prow once more to Thinadhoo. The patient’s condition deteriorated steadily as the boat crew inched their way over the lagoon to the capital island, where their chief was buried within 24 hours.

——

Veeru Ali Didi’s death caused a wave that travelled half the length of the country up to Male’, and both Hakeem and the men who had followed his instructions on Villingili – to the letter – learned that the nation’s leader had decided to personally investigate the suspected murder of his representative.

The modernising Amin’s policies had inevitably caused some resentment in the conservative atolls. As well as controversial changes to island planning, in the form of new straight roads running through every island, he had also taken a keen interest in changing the traditional status of women in society.

Rumours swirled – as rumours do – that two of Hakeem Didi’s daughters had been handpicked by Amin to take part in his ‘Miss Faimini’ beauty contest in Male’, much to their father’s outrage.** Either way, the sorcerer was now determined to summon the most powerful spells of the ages against the man set on bringing the Maldives into the twentieth century.

Just as with Veeru Ali Didi, macabre measures were being taken as Amin started the arduous trip down to Huvadhu. As his boat, the High Scent, navigated its way carefully down the archipelago, Hakeem and his fellow fanditha men worked feverishly on their high treason. Fashioning dough into an effigy of the president, each man was instructed to eat a portion in order to end the investigation, and the young prime minister’s life.

Growing increasingly desperate and depraved as their inquisitors drew nearer, the men crept into the compound of the mosque one night, exhuming the corpses of two children and removing the livers to boil into an oil. Smearing the putrid mixture on their bodies, they hoped to become invisible to the authorities who came looking for them.

When Amin came striding down the wide main street of the island that morning, Hakeem’s powers seemed to have finally betrayed him, as would one of his accomplices soon after. The prime minister is said to have shown Hakeem’s daughter a wound on his neck, attributing at least some of his notorious ill-health to the magician’s malice.

Whether Hakeem’s prowess in the dark arts of the islands played a role in the occasionally-erratic Amin’s decision to execute him for the murder may never be known. His co-conspirators were punished for the plot but lived on to add their own accounts to today’s tangle of tales.

After being tried and sentenced for the chief’s murder and the mutilation of the children’s bodies, on the afternoon of April 7th, 1953, an unrepentant Hakeem was taken to the island of Hulhule’, tied to a tree and shot dead.

Amin Didi – by now the nation’s first president – would himself meet an untimely end eight months later, though his demise would be a result of political rather than supernatural forces.

Stories would circulate in hindsight to suggest Hakeem had predicted these events, though such premonitions would require nothing more than a familiarity with the dark arts of Maldivian politics.

*Even a fact as basic as whether President Amin personally came to investigate in Huvadhu is contested, with multiple people in Gaafu Alif and Gaafu Dhaalu close to the events unable to agree upon this vital detail.

Similarly, it is unclear when the investigation was conducted. Hakeem is reported to have been executed just four months into the Maldives’ First Republic, at the advent of which Prime Minister Amin Didi became the country’s first president.

**This suggestion, reported second-hand from one Hakeem’s contemporaries, was subsequently rejected out-of-hand by another.

I would like to convey my best regards and gratitude to see such an effort put forward to uncover these historical and amazing events and stories. This is one of the best reads of late. Thanks again and wish you success in your future endeavors. ????