Keeping Time in Meedhoo

Words by Daniel Bosley; Pictures by Aishath Naj

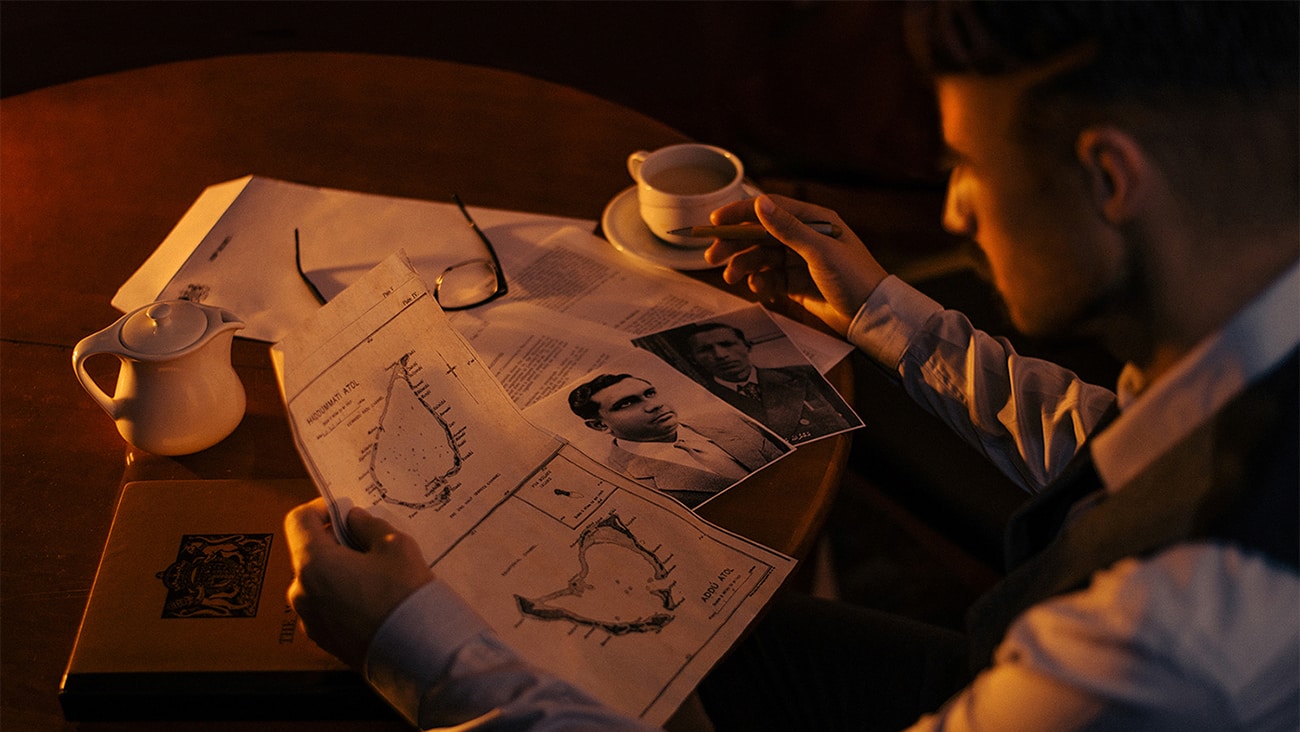

Ibrahim Didi sits on the steps of the tiny Fandiyaaru Miskiiy, built by the men who first brought Islam to Meedhoo, in the Maldives’ southernmost atoll; surrounded by the graves of their kin, who maintained the site for close to a thousand years afterwards.

The clock inside has stopped but the history is still ticking in his mind, as he recites the bloodlines of centuries and the name of every inhabitant here in the country’s oldest cemetery, Koagannu. Equally sharp despite their 86 years under the equatorial sun, his eyes scan a carefully kept notebook as he reads extracts from his 700 year family history.

His ID gives his date of birth as 1931 (on a Thursday evening, he says), though he has little use for such Gregorian details. Yoosuf Gaadir brought Islam from Yemen to his the island in Hijri 518, he explains as his blue eyes sparkle, thus beginning the island’s prominent place in the Maldives’ long and hazy history.

The finer details of a small and isolated nation’s lineage are easily overlooked, but Meedhoo’s ancient memories stretch back much further than similar countries. Without the political usefulness of ‘bigger’ histories, a small island’s stories can be washed away without a dedicated timekeeper.

Busy documenting his pious predecessors, Ibrahim’s books contain little about his own life spent in the island, though he has lived through events that make him an active part of local history as well as a steady observer.

He recalls the British military presence across the atoll when he was twelve (c.1362 AH), helping to build the runway at Gan, and his people’s fear as as they heard government guns crushing their southern rebellion from Gaaf Dhaalu Thinadhoo, 80 miles north (1381 AH).

The reach of the British Empire had nothing like the impact of its Islamic forebear, though hunger followed the closure of RAF Gan as traditional economic currents returned, beginning the steady flow of Meedhoo meehun to the capital, Male’, in the 70s.

Ibrahim stayed, filling the pages of his notebook with 44 grandchildren and tending to his beloved Koagannu. Today, young and old across the sleepy village refer specific questions about its illustrious past to his encyclopedic talents.

Government cuts have left Koagannu without a permanent caretaker, though Ibrahim – undeterred by the oppressive mid-morning heat – is happy to cycle the sandy lanes from his home to quicken the local saints once more. Both sun and history burn brightly as he plies his trade.

Leave a comment