Tales From Port T

Words by Daniel Bosley; Pictures by Aishath Naj

Long after the Maldives had became a British protectorate, but just before foreign forces would take up permanent residence there; before the village of Gan became RAF Coral Command; and before the southern extreme of ‘Suvadive’ became known as Seenu, Addu atoll was – albeit briefly – ‘Port T’.

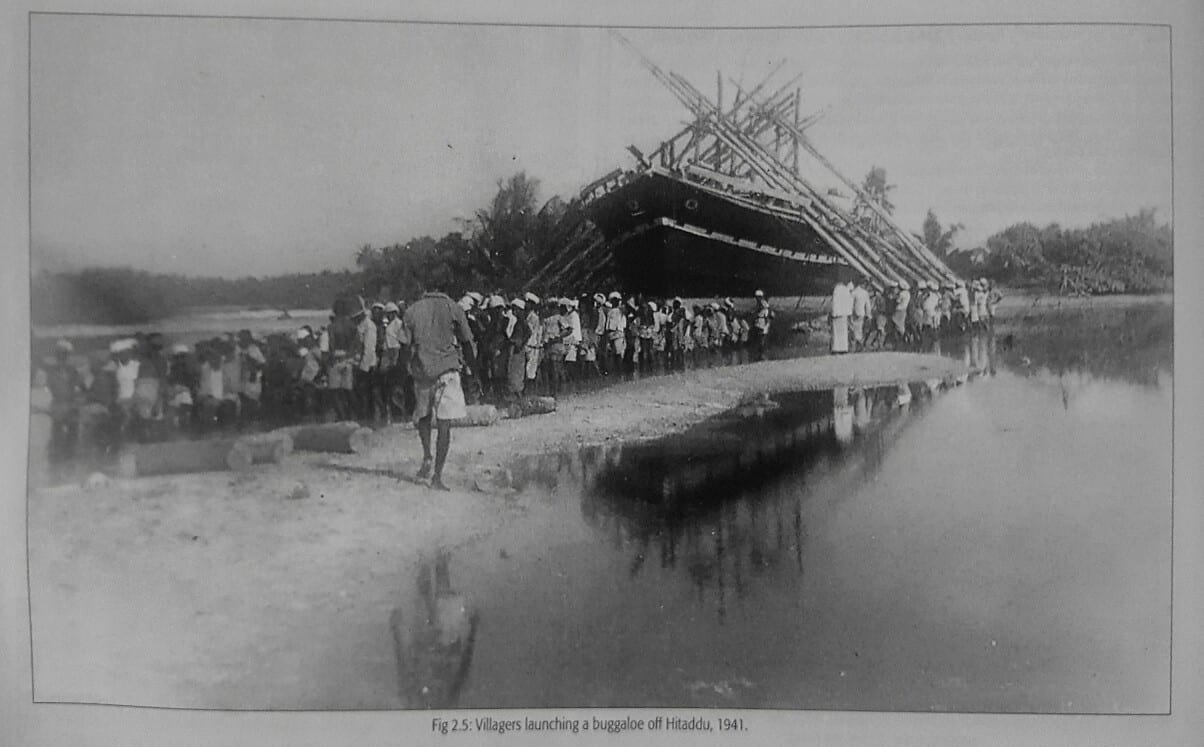

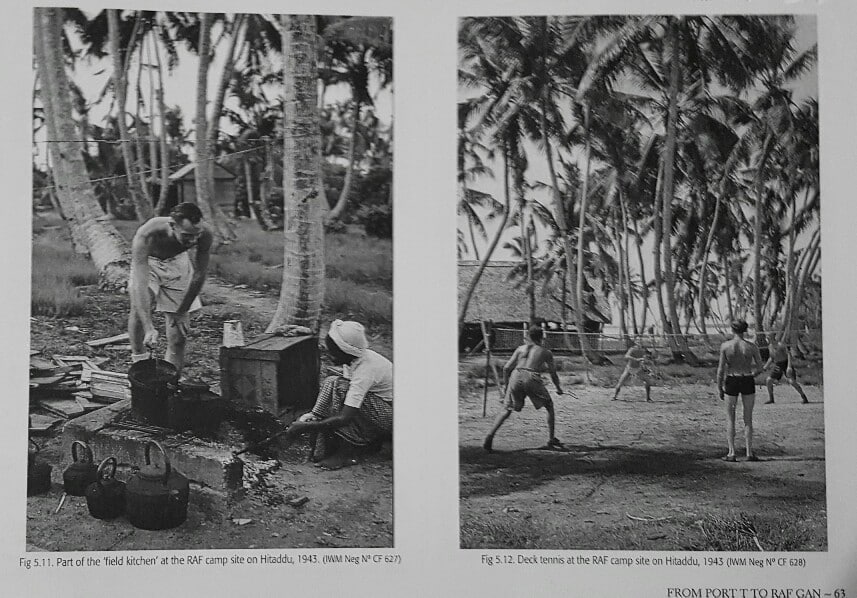

From 1941 until 1946, British armed forces transformed the islands into a giant base, from which to check Japanese incursions into the Indian Ocean. Originally conceived as a base from which to launch flying boats, the presence expanded to 4000 troops by 1943 before the theatre of war began moving east, leaving Port T redundant but Addu forever changed.

Having come across ex-RAF officer Peter Doling’s forensic account of the life and times of Port T and RAF Gan, we wanted to share a few of the great stories contained in his book, giving fascinating insights into this crucial episode in the atoll’s history.

As the British arrived in an atoll of small fishing villages, towering palms and little else, establishing communications across the islands was vital for the base’s effectiveness. Meeting the requirements of the three branches of the armed forces present was tough, eventually requiring over 40 miles of submarine cable and a further 30 miles on the land.

After painstakingly training Addu islanders to install the cables, and the loss of at least one boat during the work, progress was slowly made. But, after overcoming the challenging environment and skills shortage, efforts were still being hindered; only this time, foul play was suspected.

On repeated occasions, troops would lay hundreds of yards of cable, only to find them chopped into pieces when they returned the next day. Overnight watches were arranged, though weeks would pass before the culprit was apprehended.

Eventually, the investigations located the saboteur; a young girl from one of the villages. Described as suffering from mental illness, the girl had been attacking what she believed were snakes during the night (though this was perhaps a fair assumption from her perspective). With the villagers unable to explain to her the consequences of her actions, they had no choice but to keep a close eye on this surprising saboteur from then onward.

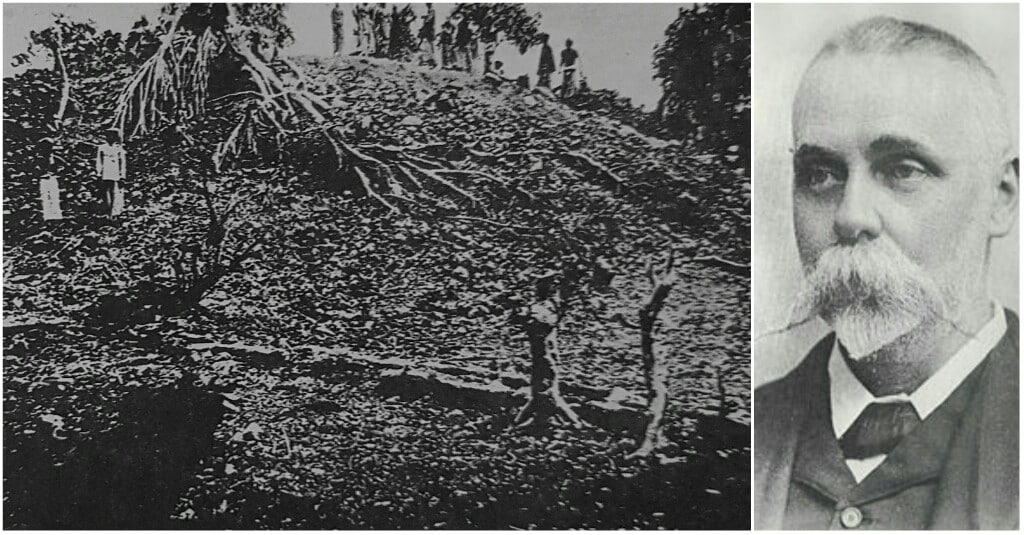

Bell’s discoveries of Buddhist remains in Addu, Fuvahmulah, and Laamu atolls – as well as his thorough study of island history and culture – were published in full in 1940, though the limited copies available would eventually send the price of one rocketing to $10,000.

It therefore seems unlikely that the archaeologist’s namesake, Major Kenneth Bell, had read the book before he arrived as part of a company of Royal Marine engineers in 1942, charged with clearing space on Gan for a proposed runway at Port T.

The surprise of Major Bell’s marines when confronted with a mound just under 30 feet in height (the Maldives’ average elevation is less than eight) suggests they had not done their homework either. Pausing temporarily to assess the inconvenience, the under-pressure engineers proceeded to flatten the structure; a thousand years of history sacrificed to the war effort.

Bell’s 1922 work at Gan had been cut short by a tight schedule and lack of tools. It seems likely that anything of historical interest unearthed during the WWII ‘excavation’ would have been used to lay the airstrip, for which 10,000 cubic yards of crushed material were required.

Perhaps fortunately, Bell the archaeologist had passed away five years earlier (aged 85), having spent his final days – and his failing eyesight – attempting to complete his Maldives monograph. He never lived to see the work overseen by his namesake.

The village areas were clearly demarcated as out-of-bounds to servicemen, particularly after some had reportedly entered local houses and taken pictures against the wishes of the occupants, who were said to be frightened of being photographed. Maldivian labourers were provided to help with the base’s construction, though the British camps were off limits after hours.

None of this stopped off-duty contact between the two groups, however, who soon struck up a black-market trade in cigarettes, soap, coconuts and fish. Though the women were said to be shy and to keep their distance, the greatest fear amongst leaders on both sides was that opposites would continue to attract (two decades earlier, Bell had commented more than once on the general boldness of island women).

The base’s standing orders were subsequently written as follows:

The Sultan of the Maldives has made a gift of as much free native labour as shall be required. In return it has been promised that no native women will on any account be molested. All MNBCO personnel will avoid all contact with native women.

These regulations were supplemented no doubt by additional health warnings allowed to circulate among the troops. Firstly, the threat of venereal disease – often reported as a problem on the islands – was made clear. But perhaps as effective a deterrent were the graphic descriptions of mutilations said to be inflicted upon any outsiders caught in the act.

Despite salacious rumours that exist in the islands to this day, the rules seem to have been followed.

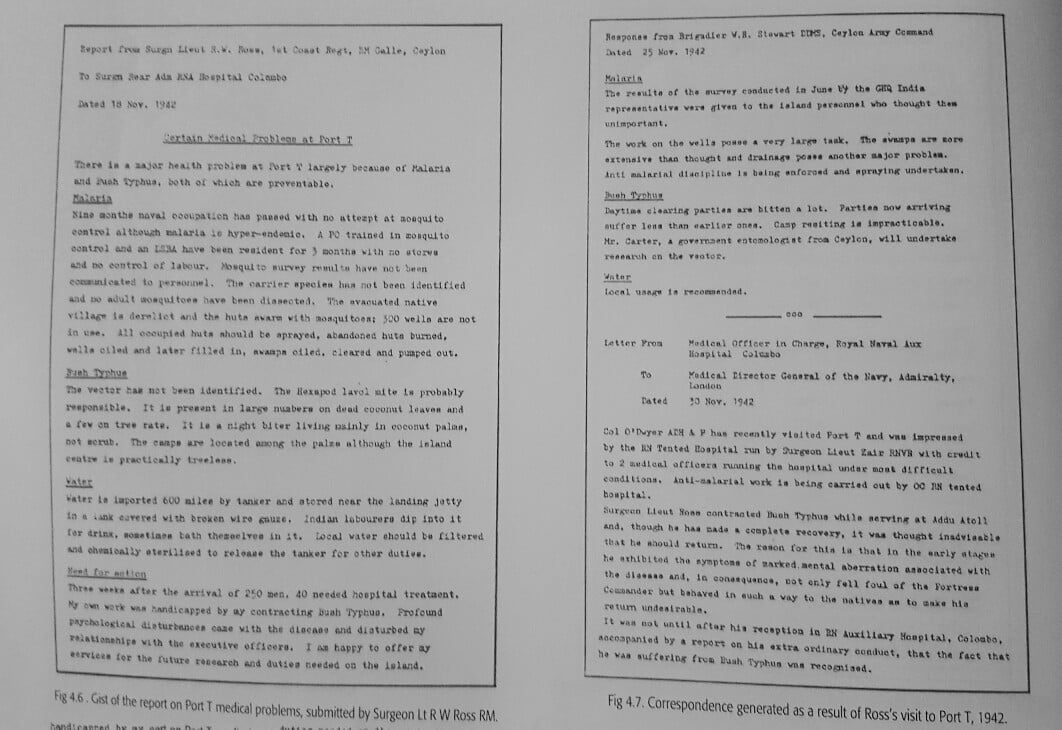

Seeing little improvement in overall health, it was decided to conduct a full health survey of the atoll and the perfect man was soon found in nearby Ceylon; bacteriology specialist and service volunteer Surgeon Lieutenant RW Ross. But Ross’s time in the islands would be short if not spectacular, reverberating all the way back to London.

Soon after arriving, Ross was reported to have started acting erratically, coming into conflict with senior officers and locals alike before those in charge felt they had no choice but to restrain him and send him home. It was later discovered that Ross had fallen victim to one of the very illnesses he had been sent to analyse. Before this was realised, his severe psychological disturbances had led to a flurry of bizarre and aggressive behaviour which had alienated most of Port T.

Upon his return to Ceylon, the diagnosis of typhus was made, and yet officials still recommended that he not return after the manner in which he treated the islanders while suffering from the illness. Specific details of his mania are unknown, but must have set tongues wagging on the quiet islands for years afterwards.

Ross did not return, and the health survey was never completed.

(All above images, unless otherwise stated, were taken from Peter Doling’s ‘From Port T to RAF Gan‘)

Leave a comment