Innes and Islands

Words by Daniel Bosley; Pictures by Aishath Naj

Stories from the atolls are becoming more common than ever, as foreign tourists are welcomed into Maldivian communities, and encouraged to share their experiences so that more might follow.

But, in 1963, it was still an extraordinary thing for a tourist – particularly a writer – to be let loose in the islands…and particularly in Addu at the height of the Suvadive rebellion.

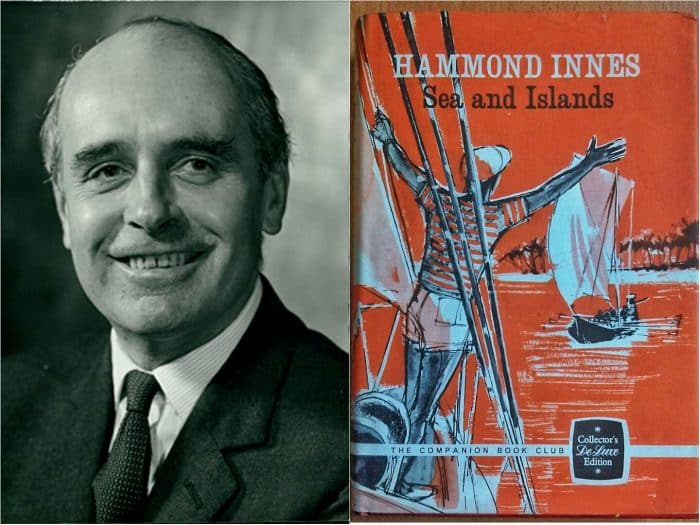

The English author Hammond Innes is better-known in the Maldives (for those who do know him) for penning the only English-language novel set in the country – 1965’s The Strode Venturer. But how and when did he do his research?

The answer can be found in his less well-known 1967 travelogue, Sea and Islands, which gives a rare, a frank, and a perceptive account of Addu during the political crisis.

My request to visit the islands came at a bad time. The RAF had been accused by the Male’ Government of fostering rebellion. Long conferences at the Air Ministry finally resulted in the RAF agreeing to give me facilities for visiting the islands provided that the political situation did not form an integral part of any novel that might result.

–Sea and Islands

Whether The Strode Venturer stuck to this agreement or not is debatable. An action thriller that flits between the London boardroom of an ailing shipping company and the middle of the Indian Ocean, the plot revolves around the maverick Peter Strode’s attempts to secure economic independence for the breakaway islands.

In Sea and Islands, Innes remarks on the “strange coincidence” that his novel was released on the exact day the Maldives’ independence was officially declared – July 26th, 1965. (Though some coincidences are stranger than others).

Close to Paradise

Both the travelogue and the novel make clear that Innes was very much taken with the atoll, the people, and perhaps the cause.

Addu Atoll is as near to an island paradise as you will find anywhere in the seven seas…But it is the Adduans themselves who are largely responsible for the happy atmosphere of the place. There are over 7,000 of them on Addu atoll – a small, dark, sensitive people, full of laughter.

His admiration for Addu’s leader, Afif Didi – “a born politician, an opportunist, and tactically clever” – is clear. Indeed, the fictional hero Peter Strode’s desire to bring about an economic miracle in Addu seems to hint at Innes’ own fantasies. Afif had told him of dreams to attract British investment in a tuna cannery (Strode, more dramatically, targets volcanic mineral deposits). In reality, by early ‘63 the dire reality of the Addu Trading Corporation’s finances were becoming clear.

[Afif] was fishing in waters too big for him. Economically he was not a free agent and this was his weakness.

Innes’ dismay at the impact of “crippling” taxes from Male’ could be seen in his observations of the trading boats (vedi) piled up and rotting on the beaches of Meedhoo and Hithadhoo; though his depiction of them as the most “pathetic” sight he’d ever seen could have been the sailor, rather than the politician, in him.

In addition to a novelist’s obvious appreciation of a tropical island rebellion, he also took a more analytical view of the situation when writing up his travels:

[T]he price people had to pay for independence was a very high one. They were completely cut off from their own kind, isolated and at the mercy of benevolent strangers, their vedis lying rotten on the beaches like the dried fish in the store.

Bearing ‘Benevolence’

Despite these insights, and acknowledgement that Gan could be vital for Britain’s global power, Innes may have overlooked the impact the base’s presence was already having on local life. By the time of his visit, fully ten percent of the population had already left traditional occupations to work on the base, and British government records from the time of the revolt indicate more indifference than ‘benevolence’ regarding the local populace.

Written at the height of the Cold War, and by a World War II veteran, Innes reflects on the status of Gan from a British perspective (“us”), suggesting the base would need to be expanded should the empire continue its terminal decline.

Regardless of all he’d seen and admired in the people, environment and culture of the atoll, the pragmatist in Innes appeared to conclude that it was Addu’s geography and structure – uniquely suited to military purposes – that would have the strongest bearing on its future.

So far they have taken the abrupt incursion of the twentieth century into their island solitude in their stride…The happy nature of this people and their cultural life has thus been kept inviolate…Their future thus hangs in the balance, the geographical position of their atoll placing them at the mercy of the world’s political pressures.

The base would close in 1976 as British military priorities changed and the impact of expansion would never come to pass. It would, in fact, be the legacy of the base’s presence and closure that would bring about another of Innes’ fears, as accelerated migration to the capital began soon afterwards.

…at least their remoteness insulates them from the problems facing so many islands I have visited – the drift of the young to the mainland centers of civilisation with its consequent disruption of family life.

Regardless of whether you agree with his conclusions, very few people have been able to write with such colour or candour about the islands, before or since, and Hammond Innes has definitely provided a rare chapter of history.

Leave a comment